Ryan O'HanlonJul 11, 2025, 08:00 AM ET

- Ryan O'Hanlon is a staff writer for ESPN.com. He's also the author of "Net Gains: Inside the Beautiful Game's Analytics Revolution."

Back in May, Arsenal manager Mikel Arteta annoyed pretty much everyone who wasn't an Arsenal fan.

"Winning trophies is about being in the right moment in the right place," he said. "Liverpool have won the title with less points than we have in the last two seasons. With the points of the past two seasons, we have two Premier League [titles]."

He was wrong and right at the same time. Liverpool ultimately won the league for the 2024-25 season with 84 points -- five fewer than Arsenal had the season before, and the same amount the Gunners accrued when they finished second in 2022-23. Of course, Liverpool landed on 84 points only because they spent the last four matches of the season partying rather than practicing -- at the time they clinched the title, they were on pace for 92 points.

And yet, it's true that Liverpool's title win was made easier by the fact that no one else came close to matching their performance level for any significant amount of time. A lot of Liverpool fans would tell you that the second-place teams from 2018-19 and 2021-22 were better than the one that just won the title -- those teams finished second only because they were competing against the greatest Premier League side of all time, Pep Guardiola's Manchester City. Same goes for Arsenal in 2023-34. They won more points than 20 of the Premier League's 33 title winners; they just happened to be competing against City.

The moral of the story would seem to be the same one that has characterized Arteta's Arsenal tenure: have patience. You win trophies by continually giving yourself a chance, year after year.

After not firing their first-time coach despite a couple of disappointing seasons at the start, then committing to signing mostly young players, Arsenal have now finished second three years in a row. Over that stretch, they've won 247 points -- four behind Man City and 14 ahead of Liverpool. The Gunners are the only ones who haven't won a trophy; they're also the only ones who haven't finished outside the top two.

Some pundits would have you believe that there's some kind of weird mental give-and-take that allows Arsenal to be better than 18 teams, but prevents them from being better than one more -- but we can chalk a lot of this up to the vicissitudes of the bouncing ball and the frailty of the human body. If Arsenal keep performing at this same level, they'll probably win the Premier League at some point.

But the Gunners no longer seem OK with the probabilities tilting in their direction. Based on the signings they've made this summer, it's pretty clear that something has changed. They don't want to wait -- they want to win now.

How the current Arsenal team was built

If everyone had been healthy last season, Arsenal's first-choice group of field players would've looked something like this: Riccardo Calafiori at left back, Gabriel Magalhães and William Saliba at center back, and Ben White at right back. We'll put Declan Rice, Mikel Merino and Martin Ødegaard in the midfield. And then up top, from left to right: Gabriel Martinelli, Kai Havertz and Bukayo Saka.

You can quibble with a name or two, but that's not really the point. Instead, I just want to highlight how old all of these players were when they joined the club:

Calafiori: 22

Magalhães: 22

Saliba: 18

White: 23

Rice: 24

Merino: 28

Ødegaard: 22

Martinelli: 18

Havertz: 24

Saka: 7

The Saka number is going to mess everything up, so let's bump him up to 18. And if we do that, the average age at the time these 10 players were acquired was 21.9. The oldest of the bunch, Merino, was signed for €35 million -- a fringe-starter price for a team of Arsenal's level and resources. This is a first-choice team that was built mostly via long-term bets on development, plus a couple of just-entering-their-prime-types in Rice and Havertz.

Broadly, the story of Arsenal's transformation back into one of the best teams in the world is threefold.

First, they've signed players to fit specifically into the manager's tactical plan. Second, they've signed players who were likely to improve after they joined the team. And third, they had a guy who joined the club when he was 7 turn into one of the best players in the planet at the most premium position in the sport. Saka's emergence has likely saved the club at least $100 million.

It sounds simple enough, but you can count on one hand the number of clubs that commit to the first two things over a span of multiple seasons. When you do both of those things well enough -- plus you don't completely whiff with bad players, and your coach's ideas aren't actively making the team worse -- you see what Arsenal saw in each of the previous three seasons: steady improvement.

In 2021-22, Arsenal were the youngest team in the Premier League (average age of 24.4, weighted by minutes played) and finished the season with 69 points. In 2022-23, they were slightly older (24.7, tied with Southampton for youngest in the league) and significantly better: 84 points. And in 2023-24, they got slightly older again (25.0, third youngest) and significantly better again: 89 points.

It seemed that Arsenal had built a team of players who would all get better together every season, and they'd keep adding players who fit that mold.

Liverpool, meanwhile, had just lost their transformative manager Jurgen Klopp, an all-time great, while Manchester City were hanging onto first place with an aging squad. But then the simple story stopped making sense. Man City imploded, but so did the Gunners. The team's average age jumped up to 25.8 (ninth youngest), and their collective output dropped to 74 points.

This was proof you couldn't rely on internal improvement and youth to win the league -- or was it?

0:51

Is Zubimendi Arsenal's answer for in front of the back four?

Gab Marcotti and Don Hutchison discuss Arsenal's newest signing Martín Zubimendi.

Arsenal's biggest issue was that their four best players all played significantly fewer minutes last season than they did the year before. Saliba's minutes share in the league dipped from 100% to 88.9%. Rice fell from 94.3% to 82.6%. Ødegaard dropped from 90.4% to 68%, and Saka went from 85.4% to just 50.6%.

Now, there are tactical issues with Arteta's approach. He doesn't embrace enough risk, especially over a 38-game season where you're trying to maximize points. And that has led to a slightly less dynamic roster being built. Per physical data from Gradient Sports (formerly PFF FC), just one Arsenal player (Gabriel Martinelli) ranks among the top 100 fastest players in the Premier League.

But that's all stuff on the margins, worth maybe a few points in either direction from season to season. The primary reason Arsenal had 14 fewer points last season than they did the year before: Their best players weren't on the field as much.

Do win-now signings work in the Premier League?

At this point in the summer, Arsenal have announced two new signings: 31-year-old midfielder Christian Nørgaard from Brentford and 26-year-old Martín Zubimendi from Real Sociedad. Per ESPN's reporting, they're close to sealing a deal for 27-year-old striker Viktor Gyökeres from Sporting Lisbon, and they're in discussions with Crystal Palace about acquiring their 27-year-old attacking midfielder Eberechi Eze.

Now, these aren't the only players they're looking to acquire. They've made an offer to Valencia for 21-year-old center back Cristhian Mosquera, and they're also negotiating with Chelsea for 23-year-old winger Noni Madueke.

But let's say they sign all of these guys. It's unlikely, but it still works as an example for this exercise. Those six players would average 25.8 years old -- almost a full four years older than the mean age of Arsenal's first-choice players when they were acquired.

Maybe that's due to the arrival of a new sporting director (Andrea Berta from Atletico Madrid), or maybe the club is sick of finishing second. Wherever the reason, it's a significant change in the club's team-building approach -- but will it work?

A lot of that depends on the individual players.

Among the two already-signed players and the one likely-to-be-signed player, Nørgaard has been one of the more underrated players in the league since Brentford were promoted in 2020. Some of this is playing for Brentford, who strip out all of the unnecessary things we can't be mathematically sure lead to goals, but Norgaard does all the things we know lead to winning -- and nothing else. He wins the ball a ton, is great in the air, gets into the box, takes shots and passes the ball forward.

Zubimendi doesn't pop in any statistical measures, really, but Liverpool thought they'd signed him last summer. And Liverpool are as good as anyone, at any level, at identifying talent. My guess is they thought Zubimendi could bring some tactical intelligence and tempo setting to their midfield. I'm less sure that Arteta's uber-control structure will get as much value out of Zubimendi's hidden, no-stats-all-star profile, but if Liverpool thought he was a winning player, they're one of the few teams I'm not going to doubt.

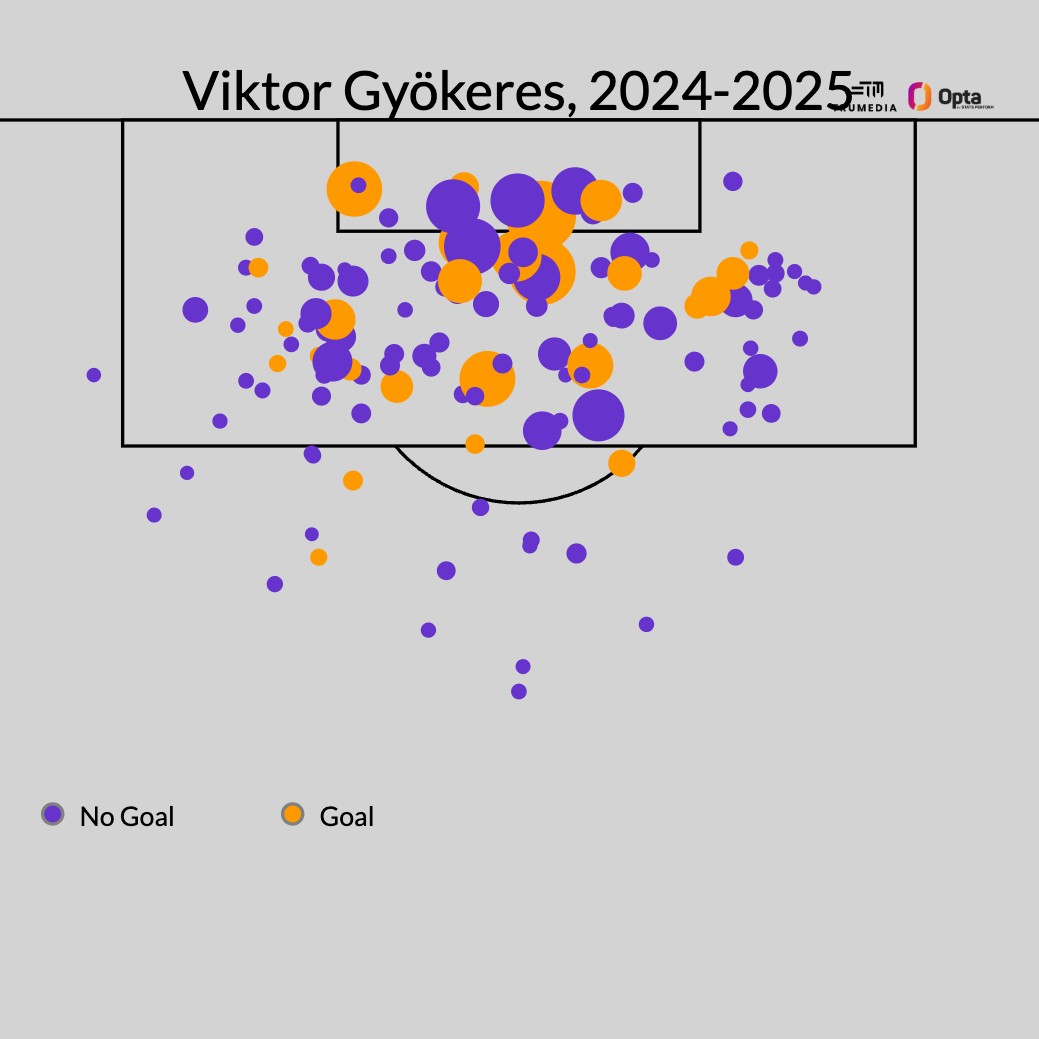

I have more doubts about Gyokeres, who put up 0.56 non-penalty expected goals and assists per 90 minutes as a 24-year-old in the Championship two years ago. That's exactly Havertz's output in two years at Arsenal -- except he did it in the Premier League. However, Gyokeres is one of the fastest strikers in Europe -- something Arsenal could use -- and his numbers exploded with Sporting Lisbon in Portugal.

However, of the 39 goals he scored in the Portuguese league last season, just one came against Benfica or Porto, and 31 came against the bottom 11 teams in the league. Most ranking systems have those clubs rated around the relegation level in the Championship.

But let's put aside my evaluations of these players. All three could work out, or they could all flop; the reality will likely be somewhere in between. Instead, it's more useful to look at these moves more broadly. How often do similar moves lead to trophies?

We can put Nørgaard to the side. He's a depth signing and will only play a significant number of minutes if someone gets hurt -- plus the transfer outlay won't have any kind of significant impact on Arsenal's future financial flexibility. But the €70 million fee for Zubimendi and a similar fee for Gyokeres are both big bets on players who'd be expected to become starters for a club that wants to win the Premier League and the Champions League next season.

Two years ago, I looked at the makeup of the starting lineups in each of the previous five Champions League finals. What I found is that those players joined their clubs at an average age of 23.8. More than half of the players signed with their teams before their 24th birthday and more than 80% joined before their 27th birthday. In this year's ESPN FC 100, players were acquired by their current clubs at an average age of 22.7, while more than 40% joined before their 21st birthdays

Take the most recent Premier League and Champions League winners, too. Among Liverpool's 18 most-used outfield players last season, Virgil van Dijk joined at 26, Mohamed Salah joined at 25, Luis Díaz joined at 24, and everyone else was 23 or younger.

With PSG, Fabián Ruiz and Ousmane Dembélé were 26 when they signed; the rest of the starting lineup in the Champions League final signed when they were 23 or significantly younger. But even among those players, I'd argue that van Dijk, Salah and Ousmane Dembele are all generational outliers: an all-time great center back who peaked later than normal at a position that peaks later than others, an already world-class and indestructible winger who teams undervalued because Jose Mourinho didn't like him, and one of the most talented players of the modern era who could just never stay healthy.

The reality is that it's really hard to find players in this age range who can make a title-challenging team better. Some of that just comes from the wisdom of the market; if these players were capable of performing at a title-winning level, they would've already been signed by a big club. Another chunk comes from the investment required; at 26 or 27, these players are, by definition, established names who have already put in high-level performances, so they're really expensive to pry away from their previous clubs. And then there's the opportunity cost down the road.

Despite the existence of VVD and Salah, most players, even the best ones, peak between the ages of 24 and 28. I know that's hard to believe, but that's just how this sport works. When you're signing someone in the back half of his prime, you're usually guaranteeing that you're not getting all of that player's best years. These players tend to have lower ceilings, too, so you don't get the superstar upside of a younger player. There's probably a lower chance that these players completely flop, but it's still possible. And if they do flop, you're stuck with an expensive, older player with a large transfer fee that you won't be able to make back. That then limits your spending power in the future.

This down-the-line flexibility is especially important for a club like Arsenal, who have four massive contracts coming up. Saliba and Saka's deals end after next season, while Rice and Odegaard's deals expire the year after that. All four of them will rightfully expect significant raises that make them among the handful of the highest-paid players in the league.

Now, trophies are the whole point of this thing. And I totally understand Arsenal thinking they had to cash in their chips after three incredibly frustrating second-place finishes. If you're confident that Zubimendi and Gyokeres and possibly Eze are the guys that get you over the hump within the next two seasons, then you go for it. But by going for it, you're suddenly shortening your title window and potentially tying up resources you need to use down the line.

And even if each signing works out, there's still a good chance that someone gets hurt, the ball bounces a certain way, or one of the other 19 teams hits an even higher level than you do. The way to increase your chances of winning, then, is to make sure you're in contention for as many years as possible. Lifting a trophy is all about timing, after all. And Mikel Arteta knows that better than anyone.

6 hours ago

2

6 hours ago

2